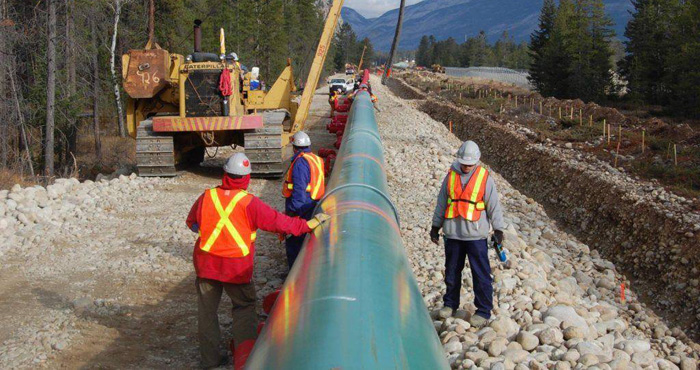

The decision by the Trudeau government to purchase the Trans-Mountain pipeline for $4.5 billion and the commitment to actually build the pipeline can hardly be seen as anything other than a massive subsidy to Oil Sands development. In Canada we have recognized that oil development is to be done by the private sector. Now, however, Kinder Morgan, who was to invest and expand the Trans-Mountain pipeline, has been thinking, that it might not be able to complete the pipeline – the risk was too high – due to opposition to the pipeline. That would, of course, not please its investors. The question the Trudeau government now has had to deal with was, how to reduce this risk. There were a number of options, and the media, in anticipating how the government would deal with this risk, suggested several alternative ways of dealing with this, but in the end the government chose the buyout – to deal with the risk by assuming it entirely.

I find I am critical of this decision for several reasons.

It is true, of course, that by making the pipeline a government pipeline, it is greatly increasing the likelihood that the pipeline will be built. One of the dilemmas our societies face is that all too frequently economic development and environmental protection are at odds. This is not necessarily so, but usually government regulation is needed to ensure that economic development does not result in environmental damage. So when government becomes the proponent of a particular development project, there is a tendency for that same government to weaken environmental regulation. This is just how it works. In the early years after perestroika, I had occasion to visit Russia. I was appalled at the conspicuous pollution there – much worse than anything I had ever seen in Canada. There is general consensus that this is what happens when the regulator becomes the proponent. In this case, because the Canadian government has now become the proponent, we are almost assured that environmental regulation will be weakened.

The decision to purchase the pipeline also reflects unfortunate tunnel vision. This tunnel vision began with the people who have stood to gain most from an expansion of the Oil Sands Project, this restricted vision then expanded to the people of Alberta, then to Alberta Conservatives. Ultimately Rachel Notley became the standard bearer for this restricted vision – the need to have this pipeline if Canada is to prosper. It was, and is, according to this tunnel view, necessary because of the jobs it will bring and the prosperity it will bring to Alberta first, and then Canada. But that point of view avoids two important questions: is this the only way to get jobs; and, are we all best served by the jobs thus created?

What if, instead of investing this money in a pipeline and the oil industry, the government were to invest a similar amount of money in a different industry, say green job development (although it would not need to be green development). Obviously such an investment anywhere, no matter where, would result in a huge number of jobs. Furthermore steps could be taken to ensure that these jobs would contribute to quality communities and desirable activities. Let me just suggest one possible scenario. Other scenarios could be considered. According to Wikipedia, 40% of all new car sales in Norway in 2017 were electric cars. In 2013, Chinese bought 17,000 new electric vehicles. In 2017, Chinese bought 777,000 electric vehicles. In both cases this emphasis on electric vehicles is the result of government promotion and subsidy. I dare say, the money being sunk into this pipeline could create many jobs promoting alternatives to oil consumption.

Had our government decided to support job development rather than oil development, those who already have invested in oil development would have suffered, but the rest of us would all be better off. There is little doubt in my mind that 20 or 30 years from now, when historians look back at this decision, it will be seen as one of the worst decisions made by a Canadian government.